- Home

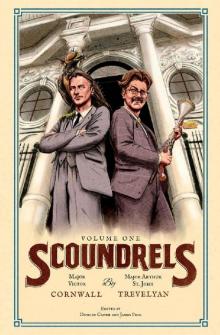

- Victor Cornwall

Scoundrels Page 2

Scoundrels Read online

Page 2

This cocaine was sensational.

It was 1950. I was twenty-nine years old and in the prime of my life. Everything I did was an immediate success. I was a notable ladies’ man, bon-viveur and poet. In fact, I’d written my first book of unpublished poetry the year before and was shaping up to be better, pound for pound, than Byron, Shelley and Wordsworth. I’d read some of their poems and most of them didn’t make any sense.

I considered myself a master craftsman. As a blacksmith forges horseshoes out of rubbish bits of metal, I could forge poetry out of rubbish words. I’d noticed this was even truer when I’d had some cocaine. By now my heart rate was at full speed and I began pacing the hotel suite like a jungle cat in a cage.

Random words began to infiltrate my thoughts. Ideas formed and were instantly replaced by better ones, as my synapses fired at lightning speed, making connections. Bloody clever ones too. Inspiration overwhelmed me and I suddenly felt compelled to write. I sat down quickly at the desk and allowed the words to come to me. I was finding stimulation in the view, in the cocaine, in Paris, this beautiful city that had captured my heart.

Cocaine Balcony. (1950)

Like le Coq,

Atop,

My Cocaine Balcony.

Streets soaked,

From Gallic tears.

Fears, jeers,

In bleu, blanc, rouge.

Sparkly sparkles,

Dans la rue de revolution.

My heart bursts.

Today I shot a dog,

From atop,

My Cocaine Balcony.

I re-read it and smiled to myself. It captured my feelings perfectly.

I walked over to my bedside table and picked up the antique silver pocket watch that had been a gift from the Sultan of Brunei. With my thumb I flicked open the lid and read again the inscription inside:

‘For my dearest Victor. I will always have time for you.’

I smiled and checked the watch face. 7.58pm.

It was time.

__________

The imposing gilded doors of the grand ballroom swung open as my name was announced. “Major Victor Montgomery Cornwall!” The entire room turned. There was a smattering of applause, which I acknowledged modestly. After a moment, I confidently descended the steps.

This was my natural habitat. Everywhere I looked there were red-blooded swashbucklers like myself and I glided through them effortlessly. The ballroom reeked of testosterone. It was a heady, charged atmosphere but for now it remained cordial. We all knew that grudges would be settled during the race.

I noted some of the faces. All the usual suspects were there, Batty Bratwurst, Ghantti, Steele, Darcy, Trevelyan, Fantohm-Waxwell, Percy, Baskerville, Cunningham, Mahatma Blaze and Maurice Johncocktosen. As I made my way to the bar I tuned in to snippets of conversations.

“…I shattered it in three places but still got up, dusted myself off and then bollocked him in German…”

“…loo roll is a luxury. Petrus is a necessity…”

“…It was the Tongan version of prima nocta, and I was to be the bride… ”

I ordered a glass of Krug and leaned against the bar, watching the room.

It was still early in the evening but there was already an edgy undertone to proceedings. Periford was throwing champagne flutes up in the air and shooting them with a musket I recognised from the Scoundrels armoury. A.W. Hendricks Snr was at a table with his cronies playing with a pine marten and making it lap up martinis. Jonty Pulvertaft was showing photos of himself with somebody else’s wife.

Several people had chosen to make a grand entrance by arriving on the back of an animal. Fairfax swept in on a four-wheeled sled pulled by wolves and Colonel Spencer had used his years in The Congo to finally tame a hippo. A lifelong ambition achieved. I raised my glass and nodded to him.

There was no sign of A.W. Hendricks Snr’s rhino, but the night was young.

One misjudgement came from Digby-Hogg who had tried to ride a walrus. He was now being gored to death, and despite his guttural screams most people were pretending not to notice for fear of embarrassing the poor chap. As far as I was concerned it was one less competitor to think about.

I continued to scan the room and noticed a slim chap standing at the bar on his own. There was something odd about him. He had short, dark hair, a pencil moustache, and fine, delicate features. I had a strange, unsettling feeling that I knew him from somewhere.

He saw me looking and approached me at the bar. “Checking out the competition?” he said. His voice was unnaturally deep.

“Something like that,” I replied, trying to remember who he was. His sharp suit was clearly the work of a fine tailor, but it didn’t hang well, and I felt oddly drawn to his large brown eyes. Then the penny dropped. “Bloody hell, what are you doing here?” I whispered furiously.

“Keeping an eye on you and Trevelyan. Careful or you’ll give the game away.” I’d known Stephanie Summerville for less than a year but in that time she’d had a lasting effect on me. She was without question one of the most beautiful women I’d ever met, and so far had somehow failed to respond to my advances. This was new ground to me and I was still coming to terms with it.

We mustered artificial smiles and sipped our drinks. “God knows what will happen if you’re discovered.” I said. “This is a men only event. Please tell me you’re not racing?”

“I bloody well am,” she replied. “And I’ll win too.” It was such a ridiculous comment I couldn’t help but smile.

“That’s impossible,” I said, as gently as I could. “You’re a woman…” She said nothing but shot me a pitying look. “Anyway,” I continued, “you must know I’m the nailed-on favourite to win?”

“Based on what?”

I shrugged. “Based on me being a chap who gets things done.”

“Can you navigate?”

“Yes.”

“Using the stars?”

“No.”

“What are you travelling on?”

“An elephant.”

“Brave.”

“I am brave.”

Normally I wouldn’t have engaged in this kind of badinage, but I found I was enjoying it.

“How have you calculated your rations?” she asked.

“One bottle of champagne and two bottles of red wine a day.”

“Food?”

“Of course.”

“And for the elephant?”

“What do you mean?”

“How have you calculated the rations for your elephant?”

“…”

Totally blank.

I couldn’t reply to that. I wasn’t sure what the answer was. As far as I knew, Trevelyan had sorted out that side of things. But now I felt we may not have prepared as much as we should have done.

Trevelyan and I had been paired together by Tiberius Lunk, the M.O.S. at Scoundrels, despite my protestations. Lunk suspected something was afoot and wanted us to look out for each other. I knew it would probably cost me the race. Summerville smiled and turned to walk away. “Good luck with that then,” she said before strolling off. I suddenly felt a touch deflated and let out a despondent sigh.

On cue, Trevelyan headed towards me, a great lumbering fool of odd proportions. His huge, chaotic hair dwarfed the rest of his head. Instead of wearing a watch he’d opted for a sparrowhawk that was perched neatly on his forearm. At Scoundrels that year, birds of prey were the en vogue male accessory, and when we shook hands I nodded my approval.

Then, in a bit of one-upmanship, I raised an arm and performed a sound I’d perfected in the Upper Sixth at Winstowe – a series of shrill whistling and piping notes. Everybody turned to look as a golden eagle swooped across the room. It landed on my outstretched arm and I rewarded it wi

th a caviar canapé. There was a gentle round of applause and then everyone went back to their conversations.

“Majestic Death was a gift from the Sultan of Brunei,” I said nonchalantly. “She loves killing things.” The huge bird stretched out her wings to their full span, glorying in her own magnificence. Trevelyan gulped nervously and shifted his small hawk onto his other arm, putting some distance between the two beasts. I was about to warn him about her uncompromising attitude to sudden movements, when Baskerville approached me from behind with a friendly slap on the back.

“Nice bird old man!” he said, just before Majestic Death tore off his face in a flurry of talons. Baskerville screamed in agony and stumbled away in the direction of the gents, but the remorseless raptor followed him, gliding elegantly across the room before finishing him off with a violent stab of her beak. That was two men down already and we hadn’t even got to the starting line.

Majestic Death was one of the most efficient killers I’d seen, but I’d made a few modifications to give her extra lethality. She wore a leather jerkin fitted with needle-like spikes that meant that any contact resulted in injury, as well as a spiked leather skullcap. I’d also fitted her with titanium razor spurs, sharp enough to decapitate a man if she was at full flight. I’d even commissioned Gieves & Hawkes to sew sleeves of split-link titanium chainmail into the arms of my suit, just to prevent her from lacerating me every time she landed. She was, unquestionably, the biggest bird in the room. And she was mine.

Trevelyan and I stood at the bar drinking. “Keep an eye out for A.W. Hendricks Snr,” he warned me. “He thinks you killed his younger brother.”

“I did,” I said. “That’s why I had to go up Everest.” I looked over to Hendricks, who quickly turned away. I realised he’d been pretending to ignore me all night. Something was afoot. He was probably planning to finish me off, but I felt confident nothing would happen until we were in the desert.

Little did I know how right I was.

Algiers, the next day

The starting line of the Paris to Dakar rally was a dangerous place at the best of times. But today there was an extra edge in the air. The Cock Fight at the hotel had been the amuse bouche. From here the race got serious.

We had arrived on the edge of the Sahara desert in a couple of English Electric Canberra bombers on loan from the R.A.F., only hours after the party in Paris. Many of us were still in our dinner suits and considerably the worse for wear. Trevelyan had vomited all over his chest and was nursing a bastard of a hangover and I hadn’t been to bed the previous night.

Despite this we were in good spirits as we loaded our packs onto the African elephant we’d brought as our transport. We figured there’d be some trouble along the way and decided to choose a beast that could handle itself.

The array of animals was a sight to behold: lions, tigers, camels, donkeys, a pack of harnessed hyenas. And a rhino.

A.W. Hendricks Snr had it saddled and was running it up and down the starting line in short, powerful sprints.

The pine marten I’d seen in Paris had sensibly abandoned him, and then unsensibly made friends with Trevelyan, who insisted on keeping him in his trousers. This may have been for some kind of horrid sexual gratification, but it was more likely to keep him away from Majestic Death who had killed his sparrowhawk the previous night and left its entrails hanging from a hotel chandelier.

Either way I didn’t mind. I knew it would annoy Hendricks, so I was happy to bring the little fellow along. His name was Chup Chunder. He was a European pine marten, a bonnie little chap, quite endearing and spirited.

I was about to climb up on the elephant when a camel approached. It was Summerville, decked out in desert fatigues and still passing herself off as a man. She looked down at me, “good luck. I think you’re going to need it.”

“Luck won’t come in to it, darling,” I replied. “There’s still time for you to back out. Flowers don’t bloom in the desert.” Summerville smiled and rode the camel away. I found her annoying and alluring in equal measure.

Suddenly I heard a vengeful cry.

It was Hendricks screaming at the top of his lungs, “Cornwall!”

The starting line broke apart to reveal him astride his beast in full charge. I tried to dive out of the way but was fractionally too late. The rhino caught me from behind and tossed me in the air.

St. John, to his credit, read the mood perfectly and saw this as an opportunity to gain an advantage. He shot the rhino through the skull, sending A.W. Hendricks Snr tumbling. Many took the gunshot as the start of the race. The animals went berserk. Some reared up and dismounted their riders, others simply trampled over those in their way. A.W. Hendricks Snr staggered to his feet and pulled out a pistol of his own, wildly shooting in my direction but finding no time or space to take a clean shot. It was pandemonium. Guns were drawn, swords unsheathed and rivalries renewed.

Majestic Death had taken to the air and had begun to decapitate people indiscriminately with a series of lethal dive bombs. The Sultan of Brunei had once told me that “to be killed by this magnificent animal would be a glorious honour.” But that seemed scant consolation to those who felt the sudden, grim pressure of her beak in their skull.

I struggled to my feet in some deal of pain and knew instantly that my sphincter was as slack as a torn carrier bag. I was up in time just to see Summerville dig her heels into her camel and set off. Then she pulled off her headdress and unfurled her head of wondrous obsidian hair. I couldn’t believe my eyes. She was one hell of a woman.

We needed to get going as the race was already underway. I gingerly climbed on to the back of the elephant, mewling as sharp bursts of pain shot through my smashed-in fuselage. With trembling hands I took the reins and accidentally dislodged a brace of hand grenades, which I quickly kicked away in panic, sending more pain shooting up through my anus. Regrettably the grenades landed next to Cunningham, Scoundrels’ wine sommelier, a decent chap who had the most sophisticated palate I knew. He could blind taste a wine and tell you the grape, the year, the country, the region, the vintage, the alcohol content, the name of the producer, the name of the producer’s wife and even the state of their marriage.

But he failed to move out of the way, and for the first time in his life sampled the bitter notes of TNT, barium nitrate and burning flesh, as fragments of hot shrapnel hit him in the legs.

I raised a weak hand in apology and tore the top off an ampoule of morphine with my teeth. I’m a man who can withstand his fair share of pain, but this injury had got me in a bit of a sweat. After some painful fumbling, during which Trevelyan offered absolutely no assistance whatsoever, I managed to inject the morphine into my thigh. My outlook brightened up no end.

“Right then, shall we go?” I announced cheerily, digging my heels into the elephant’s side.

As our great beast lumbered forward we could see the others in the distance, and my thoughts turned back to Summerville.

Then I remembered that some flowers do indeed bloom in the desert: desert flowers.

__________

From this point on my recollections of the events are somewhat patchy. You’ll have to forgive me but that’s the result of extreme dehydration.

After about eight days of trekking it was clear things were not going well. The elephant was dead and neither of us knew why. Perhaps we should have fed it, but St. John had assured me that elephants were known as ‘ships of the desert’, and that they could live off the fat reserves in their tusks. Neither of us knew what had happened but we knew we were in trouble. All thoughts we had of winning the race were over. This was now about survival. The desert is an astonishingly harsh environment. By day we roasted from the blistering sun, and by night we froze near to death under cloudless skies. It was hell on earth.

Luckily, I’d taken the precaution of using sun cream. The desert offered no shade whatsoever

, so without it I’d have ended up hideously burnt, like Trevelyan. After the first day his skin had blistered like a piece of bubble wrap. But by day eight he was so burnt and dehydrated that his face had completely dried out. It looked like somebody had stamped on a ginger biscuit.

As we staggered across the endless sand, he’d occasionally try to speak, but his lips cracked like the crust of a lava flow, the gaps between revealing glimpses of fiery red flesh. It must have been agony.

Thankfully I had thought ahead, packing a stick of lip balm to keep myself moist and supple. “For god’s sake man,” I said, holding it up, “All you had to do was ask. Speak up next time.”

Unfortunately it didn’t look like there’d be a next time. Trevelyan had lost the power of speech. Instead of words the only sound he could emit was the empty sound a chimney makes as the fire beneath it dies. I could tell from his buggered eyes that he was as angry and upset as I’d ever seen him. I could only shrug and offer him a sympathetic look.

That’s not to say I didn’t have my own problems. As well as having no food or water my biggest concern was my ruptured anus. The rhino had caught me plum and my stricken undercarriage was still leaking blood. Without a healthy supply of morphine I’d have been in all sorts of bother.

So, for different reasons, we needed medical help, and fast.

We continued to stumble through the desert for what seemed like weeks, hoping we would come across a village or dwelling. I could sense St. John’s frustration behind his rigid face. To cheer him, I would recite new poems in the evenings. I couldn’t soothe his skin, but I could offer a few healing words to help alleviate the pain in his mind.

__________

Broken Biscuit. (1950)

Where doth the desert begin?

And your face end?

Dusty,

Dry,

Crumbling,

Cracking,

Broken biscuit friend.

Scoundrels

Scoundrels